(Article first appeared in the Wall Street Journal on March 5, 2024)

Why People Are Switching to Their Hometown Banks

Community banks and credit unions are outperforming the banking industry as customers push back against consolidation.

By Imani Moise

Jana Dalton used the same bank for 40 years, depositing checks and withdrawing cash from the account she first opened at age 16. Now, she’s switching banks. PNC Financial Services Group, the sixth largest U.S. lender, bought her hometown bank. Two years ago, it closed Dalton’s original branch and has since shut down three nearby locations. Her newest local branch, 9 miles away, sometimes turns her away when she doesn’t sign up for an appointment online.

“There’s too many bells and whistles and we just need to back up and go back to customer service,” said the golf-course operator in Miamisburg, Ohio. Her new local bank, Farmers & Merchants Bank, has $291 million in assets compared with PNC’s $562 billion.

Some bank customers are going small, pushing back against a wave of consolidation that has concentrated deposits and loans in a handful of the largest banks. Many have found that making a switch not only gets them more face time with bankers, but they are also earning more and paying less.

People wanting a smaller bank have an ever-smaller number to choose from. Bank mergers are expected to accelerate this year as lenders seek safety in size after a series of regional bank failures in 2023.

Capital One’s $35 billion deal to acquire Discover Financial Services in February already made 2024 a bigger year for bank mergers than the previous two years combined.

A changing industry

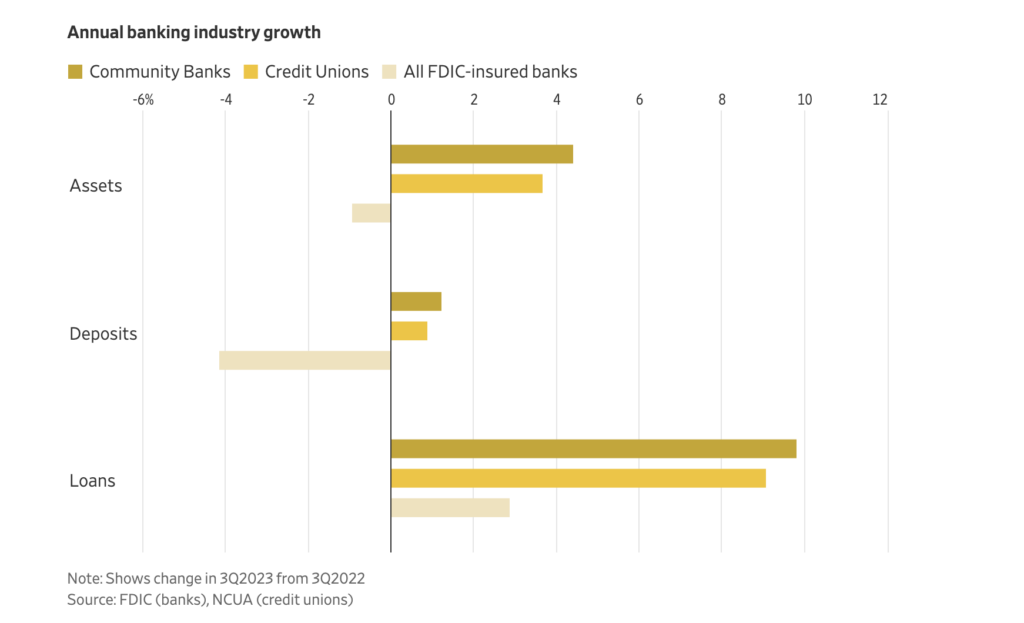

While the biggest banks are getting bigger, the smallest are growing too. Community banks, which typically have less than $10 billion in assets and a concentrated footprint, grew deposits by about 1% in the third quarter from a year earlier. Credit unions grew deposits by a similar amount. Their loan books grew by 10% and 9%, respectively. Both far outpaced the broader banking industry, according to federal data.

Midsize banks are struggling. Three failed this past year after runs on their deposits. And New York Community Bancorp has recently been under pressure.

During the tumult, large corporate clients, which often have more cash in their accounts than can be federally insured, moved billions of dollars to the biggest banks because they were seen as too big for the government to let them fail. Customers with lower balances, such as consumers and local businesses, often opened accounts at smaller banks, executives said.

“People are being a little more selective, and really going more for the convenience and the local service levels,” said Tom O’Brien, chief executive of Sterling Bancorp, a community bank that grew deposits by $50 million, or 3%, last year.

Big banks have invested billions of dollars into technology, and cut branches as most banking functions moved online. Since 2020, banks have closed more than 6,000 branches, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. Though Farmers & Merchants doesn’t have an AI chatbot like Bank of America or Capital One, Dalton says she appreciates being able to walk into a nearby branch without an appointment.

Even the biggest banks acknowledge that people like to do some banking in person. PNC plans to add new branches this year after closing more than 200 last year.

Fewer choices

Avoiding the big banks takes some work. When Doug Meekhof’s local lender in Michigan was acquired by the larger Huntington Bancshares in 1997, he moved his money back to a smaller bank. A few years later, that bank, Byron Center State, was bought by Chemical Bank, which then merged with TCF Bank. In 2021, it merged with Huntington.

Meekhof, who runs a family trucking company, moved his personal and business bank accounts to a community bank in Western Michigan two years ago. The number of banks across the country has more than halved, from 9,144 in 1997 to 4,135 in 2022, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data. Despite this, deposits at community banks were about 12% of all bank deposits in the third quarter, up marginally from a year earlier.

Rerouting all of Meekhof’s payments was time-consuming, but he is prepared to do it again in the event of another acquisition.

“With a bigger bank, you’re just another number,” he said.

Though bank failures have become rare, they are more common among smaller banks, partially because they are seen as less likely candidates for a government rescue. Many also have nursed losses resulting from higher rates.

Savers can avoid losses by making sure their account balances don’t exceed federal insurance limits.

Compared with megabanks, community banks and credit unions tend to charge lower fees on loans and pay higher yields on savings products.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in February found that credit cards from big banks tend to charge significantly higher interest than small banks do. Still, most customers prefer cards from larger issuers since they typically have better reward programs.

Smaller banks’ generally lower overhead costs allow them to offer better rates on deposits. Credit union advocates say their not-for-profit business model allows them to pass more money to customers.

Earn more, pay less

People tend to stick with their banks absent a major life change. But that has started to shift. Lofty interest rates have made moving money to high-yield accounts more compelling, and online banking has made it easier. More consumers are reporting interest in switching banks today than at any point in the last decade, according to consumer sentiment research firm RFI Global.

Last year the average 5-year certificate of deposit from a credit union paid 0.91 percentage points more interest than banks, up from a 0.19 point difference in 2013, according to the National Credit Union Administration.

Better rates alone usually aren’t enough to motivate people to switch. People tend not to pay close attention to how much they earn on savings. A few extra percentage points doesn’t always make up for the pain of switching, and some people like managing their entire financial lives in one place.

Jumping from bank to bank in search of the highest rate is probably a poor investment of time, said Rachael Burns, a certified financial planner in California. But with interest rates at the highest point in 20 years, it is a good time to take advantage of riskless returns.

“It’s certainly worth the effort of looking around now,” Burns said.

Laurie Matta, the chief financial officer for the city of Clarksville, Tenn., decided to move the city’s bank accounts from the U.S.’s fifth largest lender, U.S. Bank, after a mix-up during the pandemic. The bank accidentally credited the city for a remote deposit twice, leaving an extra $150,000 in the account. It took six months, and many unsuccessful attempts to get the bank to correct the error, even though it shared an office building with city hall.

She moved the accounts in 2022 to Legends Bank, which is down the street. There was another upside: The city’s cash earned 4% more in interest. Those yields also inspired Matta to move her personal savings accounts to another community bank from Wells Fargo.

After the switch, Matta said she got a call from her old U.S. Bank representative, who had retired a few years earlier, saying: “She was sad, but she understood why.”

Write to Imani Moise at imani.moise@wsj.com

Article first appeared in the Wall Street Journal on March 5, 2024